I wrote an article for East Anglia Bylines on my experiences attending two workshops as part of Norwich Theatre’s Fatherhood series.

recent posts

- Exploring fatherhood: how can dads do better?

- From cars to cargo bikes: how families found freedom

- “Cargo bike riders travel around the city like drivers used to in the 1950s: in style.”

- „WATER“: wenn der Wasserversorger psychische Unterstützung anbietet

- “WATER” – what Anglian Water is doing for its customers’ mental health

-

A shorter version of the article below appeared in East Anglia Bylines on 14th November 2025:

-

A new study shows that households can use electric cargo bikes to halve car miles – and a pilot scheme in Norwich is helping residents make the shift

A family participating in the ELEVATE experiment in 2023/24

What happens if you just give people electric cargo bikes?

This was the radical question researchers in Leeds, Brighton and Oxford set out to answer by lending e-cargo bikes to 49 households in suburban areas of their cities for a number of months in 2023 and 2024. The experiment with e-cargo bikes was part of a larger research project called ELEVATE that is exploring what is becoming known as e-micromobility (electrically powered devices like scooters, bikes and skateboards).

The researchers found that by using the e-cargo bikes the participants cut the distance they travelled in cars by 51%. The trial also helped convince some households that e-cargo bikes were right for them: by the end of 2024, no less than ten households had bought e-cargo bikes with their own money. The team published their findings in a paper in September, and Dr Ian Philips, the project lead and senior research fellow at Leeds University’s Institute for Transport, says he regards their work as “a positive message” for a form of mobility that is still in the early-adoption phase.

New rental scheme in Norwich

Rob Hampton, director of the Cambridge-based cycle retailer Outspoken Cycles, also believes there are a lot of people out there who could be convinced that an e-cargo bike is for them. This summer, Outspoken Cycles introduced an e-cargo bike rental scheme in nearby Norwich, even though it doesn’t have a shop in the city. The intention behind the initiative is to “grow the community”, as Rob says, and there is no expectation that participants are necessarily looking to purchase a bike from the company.

As Rob explained to me, his team realised that the outlay involved is such a significant one that households often need a while to figure out whether an e-cargo bike is really the right choice for them – and which model best fits their needs. The scheme saw strong uptake, with all bikes being lent out regularly over the summer months.

Britain certainly has some catching up to do in this field. Figures show that whilst there were just 4,000 electric cargo bikes sold in the UK in 2022, in Germany the figure was a striking 90,000 and in France it was 70,000. Dr Philips’s team also identified a high concentration of ownership in London, making their pilot in other, smaller cities insightful for assessing potential outside the capital. It is these cities that will be decisive for scaling up e-cargo bike adoption.

Outspoken Cycles has been running a scheme for businesses which recently finished; its family e-cargo bike scheme was launched in the summer.

A replacement for the second car

Whilst Outspoken’s Norwich scheme is new this summer, Rob told me they have been selling cargo bikes to the area for many years, and he has seen several cases where acquisitions have led to households selling their second car.

Liam, a former teacher from Norwich, regularly ferries his nine-year-old twins around in an e-cargo bike that starting life as a “non-e” cargo bike and was then electrified when he started struggling to get both kids up the hills. One year ago, Liam and his wife decided to take their second car off the road, as they weren’t using it anymore. When a friend asked him to transport a wardrobe recently, Liam simply turned up with his cargo bike and strapped it across the box up front.

The mobility mix

As Dr Philips is the first to admit, e-cargo bikes are not a mobility panacea. They are the right solution for “some households in some places”, as he puts it. This emphasis on place is shared by London-based transport consultant Thomas Ableman, who, together with his wife, runs the blog CarefreeCarfree.

For rural areas with poor public transport, reducing car miles can be a real problem, which is why Thomas mostly hopes to reach those living in higher-density areas. However, even in areas that are suited to e-cargo bike use, some people are still reluctant to consider it for other reasons.

Naegeen is an environmental officer at a local authority who lives in a terraced house just outside the centre of Norwich. On holiday in Copenhagen this spring with her husband and their one-year-old, Naegeen was happy to cycle around the city. “It was something about the number of people doing it; I just felt safe,” she says, “and of course the fact that there were dedicated cycle lanes certainly helped.”

Naegeen and her husband use their car daily, and whilst she would like to reduce the amount they use it, she says she would have to feel a lot safer in Norwich than she currently does in order to consider doing so through cycling.

But what about the cost?

Another potential barrier is the belief that e-cargo bikes are unaffordable. It’s one thing to participate in a funded research scheme, but quite another to shell out upwards of £5,000 to buy one of these machines yourself. Yet, when you do the maths of car ownership and e-cargo bike ownership over several years, the case is clear: a car is more expensive. Earlier this year, the Global Cycling Network ran an experiment and came to the conclusion that owning and running a car is four times more expensive than owning and running an e-cargo bike.

Dr Philips points out that for many families in financially precarious situations, the payments around their car can actually be a source of economic stress. If these families live in the right areas, e-cargo bikes might be a way to reduce car ownership and save money.

However, the academic also notes that we need to talk about the rich, given their larger carbon footprints and propensity to travel more. As he puts it, we need a two-pronged approach to equity: using creative mobility solutions to help working-class people save money, whilst also using them to get wealthy people to do their bit.

Mobility as freedom

So running an e-cargo bike is cheaper than a car. But maybe that extra cost is worth it just to have the convenience and, well, the freedom of driving? Talking to owners of e-cargo bikes, I get a very different impression.

For Liam, freedom isn’t driving. For him, freedom is traveling around the city, seeing a shop, and deciding spontaneously to pull over to the side of the road, lock up his bike and go in. As he puts it: “In that sense, cycling is a lot like I guess driving was in the 1950s. Drivers still think they can move around like that, but they can’t; we cyclists can.”

As well as being spontaneous, cycling is also more predictable. Rowan, a carfree architect with two children, points out that with an e-cargo bike, when his phone says it will take fifteen minutes to get somewhere, then he knows he can be there in fifteen minutes; there will be no queues, and he won’t have to hunt for a parking space at his destination. “Cycling is just much more reliable,” he says.

It’s also physical activity. Dr Labib Azzouz of Oxford University, who supervised the ELEVATE project’s trials in his city, spoke with several participants with children who said that since becoming parents they’d had no time for exercise. Using the e-cargo bike in place of a car allowed them to incorporate exercise into their daily routine at little to no extra time cost.

It is this emphasis on the benefits of e-cargo bike usage over driving that feels key to accelerating behavioural change, rather than the more defensive rhetoric of trying to show that cargo bike usage “isn’t any worse” than driving a car.

Going carfree

Raising children without owning a car at all is the extreme, but, as Rowan demonstrates, it can work. The blogger Thomas Ableman says it’s about adopting a fundamentally new mentality, and changing deep-set habits. “You can’t get everywhere without a car, but do you really need to?” he asks. He points out that if places like the Isle of Man and West Cornwall can be visited very easily without a car, perhaps it doesn’t need to be somewhere as far-flung as the Outer Hebrides every summer.

Security is another classic reason cited for the supposed necessity of car ownership. However, on their blog, Ableman and his wife write about how on-demand cab-booking apps can provide that same sense of security: in an emergency, they are there. Car clubs such as the Enterprise Car Club are also a way to have access to a car without owning one.

Rowan and his partner have access to his partner’s parents’ car (they actually own two, as Rowan is good enough to disclose to me), and they make use of it five or six times a year. When I ask him about his regrets not owning a car, Rowan turns the question on its head. In fact, he chuckles, his real regrets are the occasions when he and his partner “fall for the trap of thinking it will be easier with the car”. They seem to be learning, though: this summer they went camping with the kids and managed to fit everything into, and onto (!) the e-cargo bike.

New trips

Fascinatingly, the study also shows ways in which e-cargo bike usage goes beyond simply replacing car trips and in fact leads to households going on new trips altogether. In our conversation, Dr Azzouz cites one family who said that they used the e-cargo bike to go out for family rides in the evening after dinner, something they wouldn’t have chosen to do with a car. Other participants talked about trips to places which would involve parking, or traffic, meaning that doing the outing with a car would have been “too much faff”, as Dr Philips puts it, but doing it with the e-cargo bike becomes fun.

These kind of trips also chime with some of the more unexpected benefits participants cited in their feedback. Whilst many mentioned things like sustainability, convenience and health, some also mentioned a feeling of “conquest” – of having achieved something new in their lives – whilst others saw the e-cargo bike as a way to “escape” the day-to-day routine in their lives.

Dr Azzouz, who is currently exploring the nature of these new trips, sees a key area of e-cargo bike use in households with a “care element”. Caregiving often comes second to breadwinning when there is only one car available, and caregivers in the trial, frequently mothers, reported that having an e-cargo bike meant that they were independent of their partners and able to do fun things with the children during work hours.

It is precisely the non-mandatory nature of these trips that makes them so interesting, because it shows that e-cargo bikes can change how households approach mobility and place beyond a simplistic binary of car-to-bike shift.

Barriers

Of course, the study also details a fair list of barriers to e-cargo bike uptake. Some, such as better cycling infrastructure, are long hills to climb. Similarly, issues around parking and safe places to lock up e-cargo bikes require deep rethinking in planning and building practices.

Although the ELEVATE team gave all participants training in how to handle e-cargo bikes and tips on using them on roads, some still reported feeling insecure. Whilst interviewing the various families who have featured in this article, I got the impression that it’s a huge benefit to e-cargo bike uptake if cycling feels like second nature to you. This demonstrates the importance of cycling proficiency, particularly in early years, so that for future generations cycling feels like a natural choice for as many people as possible.

There are also cultural preconceptions that can be addressed. Dr Philip’s team showed that it is a misnomer that e-cargo bikes are a reserve of the rich, and studies such as the one mentioned earlier have shown that usage is cheaper than maintaining a car. Secondly, whilst more men purchase these bikes, when they are transporting children, they are more likely to be being ridden by women. Framing cycling as a form of transport for all, and not just lycra-clad men, is crucial to a democratising political project in cycling more broadly, but also to the uptake of e-cargo bikes.

Conclusion

So where does this leave us? Dr Philip’s team found that 11% of people not currently using an e-cargo bike said they could see themselves using one regularly. The fact that only 3% of English adults are using one regularly at the moment suggests potential for enormous growth in this market. Hopefully cycle retailers around the U.K. will see these figures and invest resources in more schemes to help encourage households to take the plunge.

Dr Azzouz praised the Norwich scheme from Outspoken Cycles, seeing it as exactly the “right kind of exposure” this form of mobility needs to escape the niche of eager cyclists and go mainstream.

Beyond the positive statistics, a clear takeaway from the research – and from my conversations with e-cargo bike owners – is that using e-cargo bikes is fun. Participants in the ELEVATE project commented on how easy it was to interact with their kids when cycling. They also reported high levels of interest from members of the public, with one participant saying that passersby often waved or even cheered them on.

My wife and I have an e-cargo bike and I frequently get friendly smiles from strangers as I pass by. A couple of weeks ago I was cycling our two children home from school when a man driving a white van stopped at a junction and remarked to me how wonderful it must be for the kids to be ridden around the city in this way. Such genuine enthusiasm about mobility is rare – and inspiring.

-

Heute ist Welttag für psychische Gesundheit und ich habe diesen Artikel geschrieben, um die Diskussion rund um innovative Ansätze in der psychischen Gesundheit zu fördern.

Seit Juli wohne ich mit meiner Familie in Großbritannien und, nach 14 Jahren in Deutschland, kommt mir manches hier auf der Insel ungewöhnlich vor.

In meiner Wasserrechnung vor einigen Wochen war ein Hinweis, dass unser Wasserversorger – Anglian Water – auch einen SMS-Dienst für Kund:innen anbietet, die das Bedürfnis haben, mit jemandem zu reden. Muss nicht mit der Wasserversorgung in Zusammenhang stehen, man könne über alles mögliche reden. So was gäbe es in Deutschland nicht! Nun ja, so wie die meisten Menschen, habe ich auch Gefühle, mit denen ich gerade kämpfe. Ich entscheide mich, den Service auszuprobieren.

Screenshot aus der Email von unserem Wasserversorger im September

Ich tippe das Schlagwort “WATER” ein, schicke sie ab, und innerhalb von Sekunden erhalte ich vier automatisierte Nachrichten. Zuerst eine Art Willkommen, dann einen Link zu den AGBs der Firma und den Hinweis, dass meine Daten verarbeitet werden. Dann kommt ein ziemlich nostalgischer Hinweis, dass nur Nachrichten unter 160 Zeichen bearbeitet werden können (ihr erinnert euch!). Viertens erfolgt ein Hinweis auf die Verschwiegenheitspflicht der Firma und die Info, dass eine:n Ehrenamtliche:n für mich gesucht wird. Dann kommt eine ganze Weile nichts mehr.

Für diesen Service ist Anglian Water eine Partnerschaft mit der Stiftung Mental Health Innovations eingegangen. Seit 2019 bietet diese Firma den Service SHOUT an. Es ist ein kostenloser 24/7 SMS-Chat-Service (bisher auch der einzige solche in Großbritannien), wo geschulte Ehrenamtliche SMS-Gespräche führen, um Menschen psychologische Unterstützung zu leisten. Die Stiftung finanziert sich teilweise durch Spenden, doch sie geht auch kommerzielle Partnerschaften mit Unternehmen ein.

Die Partnerschaft mit Anglian Water gibt es seit genau zwei Jahren: Sie wurde 2023 am Welttag für psychische Gesundheit gestartet. Das Modell funktioniert so, dass ein Unternehmen ein bestimmtes Schlagwort bei Mental Health Innovations kauft. Im Falle von Anglian Water ist es eben „WATER“. Wird das Wort „WATER“ anstatt „SHOUT“ eingetippt, wissen die Ehrenamtlichen bei Mental Health Innovations, dass es sich um eine:n Kund:in von Anglian Water handelt.

Das ändere gar nichts an der Qualität der Dienstleistung, erzählt mir eine Sprecherin von Anglian Water beim Telefonat. Die Ehrenamtlichen unterstützen einen genauso viel, als hätte man „SHOUT“ geschrieben und es bestehe gar keinen Zwang, über Probleme mit der Wasserrechnung zu sprechen.

Archie

Dies kann ich aus eigener Erfahrung bestätigen. Meinen ersten Versuch muss ich abbrechen, nachdem ich 30 Minuten vergeblich auf jemanden gewartet habe. Am nächsten Tag klappt es aber nach etwa fünfzehn Minuten. Ich unterhalte mich mit „Archie“ für knapp eine Stunde, und es geht in keinem Moment um Wasser. Ich erzähle ihm von meiner Einsamkeit im neuen Land, von den Schwierigkeiten, die wir alle als Familie haben, hier anzukommen. Eine Sache, die mir auffällt ist, dass es immer ein paar Minuten dauert, bis Archie mir antwortet. Das macht Sinn, denn Mental Health Innovations erklärt auf ihrer Webseite, dass die Ehrenamtlichen durch klinisches Personal beaufsichtigt werden.

Archie verwendet aktives Zuhören, Fragetechniken aus dem Coaching und vor allem viel Wertschätzung, sodass ich das Gefühl habe, ich könne mich ihm öffnen. Es erfolgt auch eine Empfehlung für einen Podcast zum Thema psychische Gesundheit. Ich verspreche, da reinzuhören. Als er sich verabschiedet, fühle ich mich tatsächlich etwas besser. Und ich vermisse ihn ein kleines bisschen. Es hat gut getan, per SMS-Nachrichten über meine Gefühle mit ihm zu reden, während ich auf dem Sofa zu Hause sitze. Intim, irgendwie.

Schreibt man „WATER“ anstatt „SHOUT“, gibt es aber tatsächlich einige Unterschiede, erzählt mir die Sprecherin von Anglian Water. Erstens kann es sein, dass man schneller rankommt (wobei alle Gespräche einer stricken Triage unterzogen werden, damit wirklich dringliche Anlässe zuerst beantwortet werden). Zweitens werden bestimmte Daten von diesen Gesprächen anonymisiert und Anglian Water zur Verfügung gestellt. So könne die Sprecherin mir berichten, dass in den zwei Jahren, seitdem die Aktion gestartet sei, die Rettungsdienste kein einziges Mal gerufen werden mussten, und dass nur in einem Fall Suizidgedanken dokumentiert worden seien. Uhrzeiten der Gespräche und „Erfolgsquoten“ werden dem Partner auch mitgeteilt.

Drittens sind die Ehrenamtlichen von Mental Health Innovations mit bestimmten Tipps ausgestattet, falls das Gespräch sich doch um die Wasserrechnung drehen soll. So können sie Kund:innen, die in finanzieller Not stecken, über relevante Unterstützungsmöglichkeiten informieren: Dass sie zum Beispiel prüfen sollten, ob sie auf bestimmte staatliche Förderungen Anspruch haben, oder wie Anglian Water ihnen mit Ratenzahlungen helfen kann. Denn wie alle anderen Wasserversorger, bietet Anglian Water solche Unterstützung an, falls man in finanzielle Schwierigkeiten geraten ist.

So gesehen, funktionieren die Ehrenamtlichen von Mental Health Innovationsals eine Art erweiterte Kundenbetreuung für Anglian Water.

Wie Anglian Water auf die Idee kam

An dieser Stelle eine kleine Geschichte der britischen Wasserversorgung, die in den letzten Jahren für viele Schlagzeilen gesorgt hat. 1989 wurde die Wasserversorgung in Großbritannien von Margaret Thatcher privatisiert. Nach Brexit wurde 2020 die Regulierung der Wasserversorgung in nationales Recht überführt. Im gleichen Jahr wurde in einer großen Studie festgestellt, dass aus allen 4600 getesteten Gewässern des Landes (Flüsse, Seen, Wasserwege) kein einziges sauber sei. In den Jahren danach bildeten sich viele Gruppen in der Zivilgesellschaft, um auf das Problem der Verschmutzung der Wasserwege aufmerksam zu machen. Etwa The Telegraph und die BBC berichteten über großen Zuwachs von illegalen Abwassereinleitungen. Erst Juli 2025 wurde ein von der Regierung in Auftrag gegebener Bericht veröffentlicht, der zu dem Schluss kam, es sei nötig, den Ombudsmann für die Wasserversorgung „Ofwat“ abzuschaffen und neue Regulierungsmechanismen zu entwickeln. Das ist also der Hintergrund, vor dem Anglian Water sich entscheidet, diesen neuen Service für mentale Gesundheit zu starten.

Am Telefon erzählt mir die Sprecherin, wie die Firma auf diese Idee kam. Während der Inflationskrise nach der Pandemie probierte Anglian Water eine Kundenberatung über WhatsApp aus, die positiven Anklang fand. Viele Menschen hätten es bevorzugt, zu tippen anstatt zu sprechen, berichtet die Sprecherin. Erstens wegen dem zeitlichen Comfort, aber zweitens weil es manchen Menschen leichter fiel, sich (digital) schriftlich auszudrücken anstatt mündlich. Drittens könne ein schriftlicher Austausch privat erfolgen, sodass zum Beispiel kein anderes Familienmitglied das Gespräch mithört. Aufgrund dieser positiven Erkenntnisse entschied Anglian Water sich, noch weiter zu gehen und die Partnerschaft mit Mental Health Innovations einzugehen.

Die Gegend im Osten von England, die Anglian Water mit Wasser versorgt, ist von psychischen Problemen geprägt. Die Sprecherin erzählt mir, dass zweimal so viele Antidepressiva hier in East Anglia verschrieben würden, wie der Durchschnitt im Land. Die teilweise sehr abgelegenen Dörfer sind für Einsamkeit sehr anfällig. Aber ein zweiter Faktor kommt dazu: Durch den sehr hohe Anteil an Immobilien, die als Zweit-Häuser von Reichen gekauft werden, wird die örtliche Bevölkerung noch weiter ausgedünnt. Tatsächlich belegen offizielle Statistiken, dass North Norfolk nach dem Zentrum von London der zweithöchste Anteil an „second homes“ in Großbritannien nachweist: Fast jede zehnte Immobilie.

Mehr als nur gesellschaftliche Unternehmensverantwortung

Manche würden an dieser Stelle behaupten, das sei nur Image-Pflege – sogenannte Gesellschaftliche Unternehmensverantwortung (auf Englisch: Corporate Social Responsibility – kurz: CSR). Doch ich glaube, in diesem Falle, dass dies nicht ganz zutrifft.

Typischer Weise besteht CSR darin, dass ein Unternehmen Geld an eine Stiftung spendet, oder Spendenakquise für sie selber betreibt. Damit kann ein Unternehmen zwar angeben, aber direkten Wert erhält er dadurch nicht.

Wenn es herkömmliches CSR wäre, Anglian Water würde vielleicht Geld an Mental Health Innovations spenden, und dafür in ihren Kommunikationen deren Service SHOUT bewerben dürfen, aber sie würden es eben wahrscheinlich als SHOUT bewerben. Dass sie stattdessen ein Schlagwort von Mental Health Innovations gekauft haben, bedeutet für mich, dass wir es hier nicht mehr mit CSR zu tun haben.

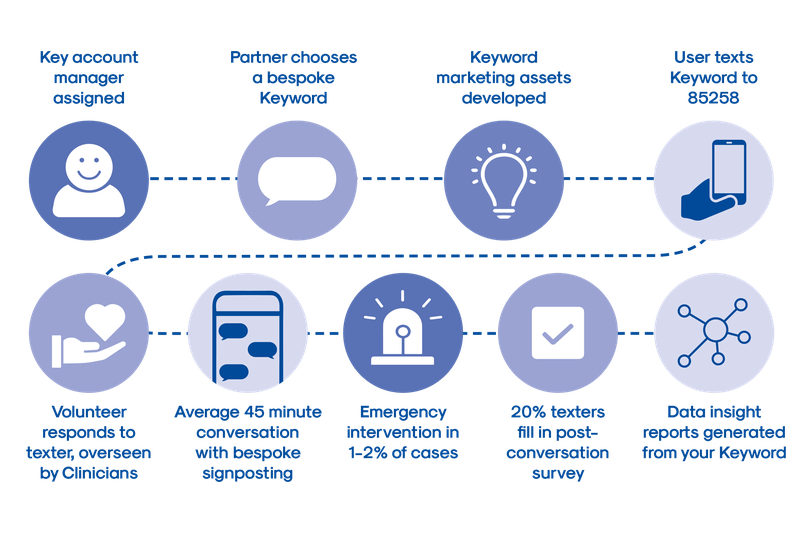

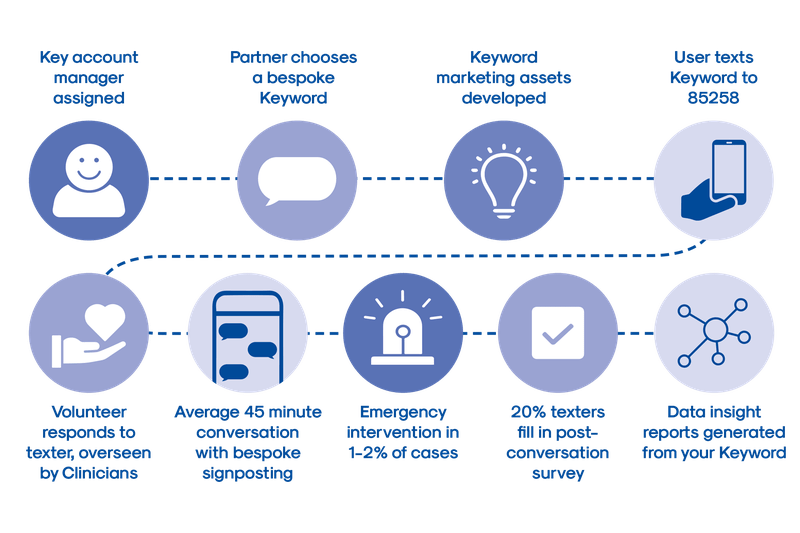

Abildung des Prozesses bei einer kommerziellen Partnerschaft mit Mental Health Innovations (Bild reproduziert mit der Erlaubnis von Mental Health Innovations)

Für mich gibt es an dieser Stelle zwei zentrale Fragen:

1. Warum fühlt sich ein Wasserversorger für die psychische Gesundheit seiner Kund:innen zuständig?

2. Warum gibt es solche kommerzielle Partnerschaften rund um mentale Gesundheit für diese Unternehmen?

Zur ersten Frage: das liegt, glaube ich, vor allem an der Normalisierung des Diskurses über psychologische Gesundheit in allen Bereichen der britischen Gesellschaft: in der Kultur, bei der Arbeit, in der Familie. Und verstehen Sie mich nicht falsch: das ist eine gute Sache. Vor diesem Hintergrund kann ich mir vorstellen, dass es sich eigentlich ganz „normal“ anfühlt, dass ein Unternehmen sich ein Stück weit für das seelische Wohlergehen ihre Kund:innen interessiert. Ja, man könnte es sogar umdrehen und sagen, welches Unternehmen würde ernsthaft sich nicht für das psychische Gesundheit seiner Kund:innen interessieren? Es ist vielleicht die logische Entwicklung davon, die mentale Gesundheit seiner Mitarbeiter:innen ernst zu nehmen. Es gehört auch zu einer breiten Transformation hin zur Prävention, und Prävention kann von vielen Parteien in vielen verschiedenen Kontexten betrieben werden. Sollte wahrscheinlich, sogar.

Die aktuelle Lebenshaltungskostenkrise (auf Englisch: cost of living crisis), die dazu führt, dass immer mehr Menschen Schwierigkeiten haben, ihre Strom- oder Wasserrechnungen zu bezahlen, hat definitiv psychische Krankheiten zur Folge. Manche würden argumentieren, dass es die Aufgabe der staatlichen Gesundheitsversorgung wäre, sich um diese Krankheiten zu kümmern (oder, dass es sogar die Aufgabe der Politik sei, diese Krise selbst zu lösen). Doch der britische NHS (die stattliche Gesundheitsversorgung) erlebt auch gerade eine Krise, im Bereich der mentalen Gesundheit steigen die Wartezeiten insbesondere. Deswegen argumentieren manche, es sei besser, den Menschen jetzt etwas anzubieten, als nichts zu tun und sie monatelang auf einen Termin warten zu lassen. Das ist, ich glaube, ein Grund, warum es Dienste wie SHOUT gibt, und warum Unternehmen wie Anglian Water dazu beitragen wollen und ihren Kund:innen helfen.

Aber das beantwortet nicht die zweite Frage, denn sie hätten dafür SHOUT als SHOUT verwenden können, ohne deren eigenes Schlagwort. Vielleicht ist die einfache Antwort hier, dass Stiftungen natürlich ihre Arbeit irgendwie finanzieren müssen, und Spenden reichen nun mal nicht so weit. Nichtsdestotrotz, womit wir es hier zu tun haben ist ein Produkt. Und deshalb, glaube ich, sollte man hier über das Kundenerlebnis reden.

Wertvolle Mentale-Gesundheit-Trends

In der Produktentwicklung geht es seit einer Weile darum, Produkte zu entwickeln, die Kund:innen lieben. Es geht also darum, welche Gefühle ein Produkt erzeugt – nicht nur welche Probleme es löst. Das ist mittlerweile sehr etabliert, und Firmen, die das gut können, wie Apple oder Spotify, sind enorm erfolgreich geworden.

Das Geschäft mit Gefühlen ist also nichts Neues. Was für mich hier aber neu ist, ist die Art und Weise wie mit, sozusagen, negativen Gefühlen umgegangen wird. Es ist die Ausweitung dieses Fokus auf Gefühle – dass man jetzt viel aktiver überlegt, wie negative Gefühle zum Leben der Kund:innen gehören, und nicht nur positive Gefühle. Das ist es, was mir hier Sorgen bereitet.

Mit ihrem anderen Service „The Mix“, der gezielt junge Menschen berät, verspricht Mental Health Innovations kommerziellen Partnern „wertvolle mentale-Gesundheit-Trends für Jugendliche und zentrale Erkenntnisse“ (auf ihrer Webseite erklärt die Stiftung, dass 75% der Nutzenden zwischen 16 und 25 Jahre alt sind). Man möchte fragen, was das für Trends sind, und warum sie für Unternehmen interessant sein sollten. (Ich habe zu Mental Health Innovations Kontakt aufgenommen, aber in der letzten Zeit waren sie mit den Vorbereitungen auf den heutigen Welttag für psychische Gesundheit sehr beschäftigt.)

Das andere, was für mich hier neu ist, ist die digitale Natur dieser Austausche, wo SMS-Nachrichten Anrufe ersetzen, was die Datenanalyse einfacher und schneller macht. Wie wir gesehen haben, Anglian Water fiel auf, dass es sich für viele Kund:innen angenehmer anfühlte, wenn sie schriftlich anstatt mündlich mit der Firma kommunizierten. Aber ohne diesen digitalen Wandel wäre die Datenanalyse viel teurer, und eventuell für Mental Health Innovations nicht finanziell tragbar als Dienstleistung. (Mancher psychologischer Experte würde vielleicht auch anmerken, dass, an seiner psychischen Gesundheit ernsthaft zu arbeiten, nicht immer „angenehm“ sein kann.)

Fazit

Auf ihrer Webseite wirbt Mental Health Innovations für ihren Service SHOUT damit, dass sie drei Millionen SMS-Gespräche geführt haben, und dass 43% der Befragten meinten, sie hätten sonst niemandem, mit dem sie reden könnten. Es ist ganz klar, dass viele Menschen Bedarf an einer Form von Unterstützung haben.

Es scheint mir zweifelsohne eine gute Sache, dass es diese Möglichkeiten gibt, und Deutschland könnte hier sicherlich einiges abschauen, was die Normalisierung von Offenheit rund um psychische Probleme angeht. Es ist gut, wenn Menschen nicht das Gefühl haben, sich für ihre psychische Probleme zu schämen. Dass ein Unternehmen wie Anglian Water Ressourcen dafür bereitstellt, für ihre Kund:innen einen solchen Service anzubieten, zeugt davon, wie weit sich der Diskurs über psychische Gesundheit in Großbritannien normalisiert hat.

Gleichzeitig kann man sich, glaube ich, durchaus Sorgen machen, in welche Richtung sich dieses Geschäft mit mentaler Gesundheit entwickelt. Erstens besteht die Gefahr, dass die hauptamtliche medizinische Versorgung sich zunehmend auf die ehrenamtlichen Versorgung stützt und die Politik ihre Kapazität und Ressourcen abbaut. Das ist aber erst mal nur ein Risiko, keine vollendete Tatsache. Aber Aktionen, die mit Ehrenamtlichen betrieben werden, sind nicht die einzige Option hier: der Ansatz namens Social Prescribing, zum Beispiel, ist auch ein innovativer Versuch, präventiver und breiter zu arbeiten, und diese Berater:innen sind viel mehr in die staatliche Gesundheitsversorgung integriert.

Zweitens kann man fragen, warum Trends in der mentalen Gesundheit für Unternehmen interessant sein sollten, und was für Produkte sie anhand dieser Trends entwickeln werden. Bezüglich der Schlagwort-Partnerschaften: Da diese nicht mehr CSR sondern Produkte sind, kann ich mir vorstellen, dass ein Raum sich öffnen könnte, wo man kreativ werden kann, was diese Produkte können und wie viel Wert sie den Firmen bringen können. Solange Mental Health Innovations die einzige Organisation ist, die einen solchen Service wie SHOUT anbietet, gibt es keinen Markt, und entsprechend wenig Druck von außen, hier zu experimentieren. Aber sollte das Modell sich als erfolgreich erweisen, könnte bald Konkurrenz entstehen, und dann könnte es sein, dass wir hier eine neue Dynamik erleben.

-

Today is World Mental Health Day and I have written this article to promote more discussion around innovative approaches to mental health.

In July my family and I returned to the UK after many years in Germany and, well, some things here are a little bit different to how the Germans do things.

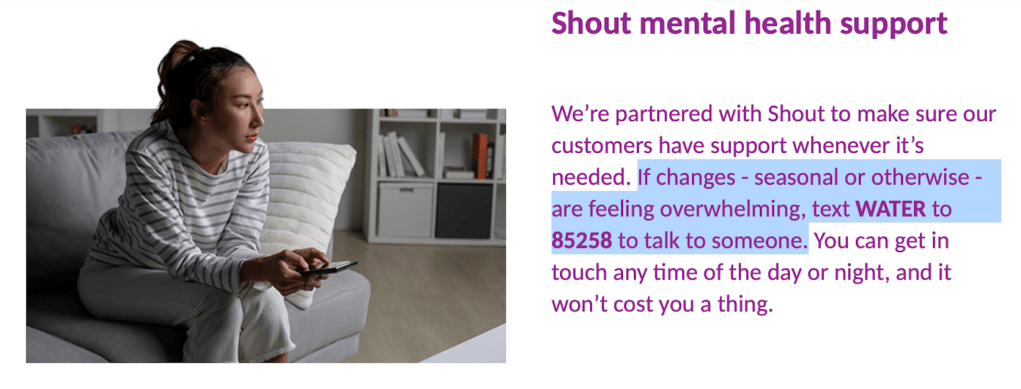

At the beginning of September I received our water bill, which included a note that our water supplier – Anglian Water – also ran a text-message chat service for customers who were struggling a bit and needed someone to talk to. It didn’t have to be related to the water supply, they explained; you could talk about anything. This was probably the least German thing I had experienced since arriving back in the country! Well, like many people, I had feelings that I was struggling with. So I decided to give it a go.

Screenshot from the email I received from Anglian Water in September

I type in the word “WATER”, hit send, and within seconds I receive four automated responses. First, a sort of welcome message, then a link to the organisation’s terms and conditions (the organisation is not Anglian Water) and that by using the service I consent to my data being processed. Then a rather nostalgic note that only messages under 160 characters can be processed (remember those days?!). And finally, a note about the company’s confidentiality policy and information that a volunteer is being sought for me. Then nothing for quite a while.

The charity that Anglian Water have partnered up with for this service is called Mental Health Innovations, who have been providing the free, 24/7 text-message chat service SHOUT since 2019. Currently the only such service in the country, trained volunteers provide conversations in order to support people struggling with their mental health. The charity is partly funded by donations, but it also enters into commercial partnerships with companies.

The partnership with Anglian Water has been in place for exactly two years; it was launched in 2023 on World Mental Health Day. As part of these commercial partnerships, a company purchases a specific keyword from Mental Health Innovations. In the case of Anglian Water, it is “WATER”. If you type the word “WATER” instead of “SHOUT”, the volunteers at Mental Health Innovations know that you are a customer of Anglian Water rather than just a member of the public.

In a phone call with a spokesperson from Anglian Water, I am told that this does not affect the quality of the service their customers are provided with. The volunteers provide exactly the same level of support as if “SHOUT” had been typed, and there is no obligation to talk about problems relating to your water bill.

Archie

I can confirm this. Although I have to give up after waiting 30 minutes on my first attempt, I have more luck with my second try, and after fifteen minutes a volunteer gets in touch. I exchange texts with ‘Archie’ for just under an hour, and at no point do we talk about water. I chat with him about my loneliness in this country following relocation, and about the difficulties we are having as a family settling in here. One thing I notice is that Archie tends to take around two minutes to reply. Mental Health Innovations says that clinical staff supervise their volunteers, so this might well explain these delays.

Archie uses active listening, coaching techniques and, above all, a great deal of praise and confirmation to allow me to feel that I can open up to him. He also recommends a podcast on mental health which I promise to try out. When he says goodbye, I actually feel a little better. And I miss him just a little bit. It felt good to talk to him about my feelings via text message sat on the sofa in my living room. Intimate, somehow.

It turns out that there are actually a few differences between texting “WATER” and texting “SHOUT”, as the Anglian Water spokesperson explains to me. Firstly, you may get through more quickly (although all calls are strictly triaged so that truly urgent cases are answered first). Secondly, certain data from these conversations is anonymised and made available to Anglian Water. As a result of this analysis, the spokesperson can tell me that in the two years since the campaign was launched, the emergency services have not been called out once for an Anglian Water client, and that only one case of suicidal thoughts has been documented. Call times and ‘success rates’ are also provided to the partner.

Thirdly, Mental Health Innovations volunteers are equipped with specific tips or signposts in case the topic of water bills does come up. This enables them to inform customers who are in financial distress about relevant ways to get help: for example, that they should check their eligibility for certain government subsidies, or look into how Anglian Water can help them pay in installments. Like other water suppliers, Anglian Water offers such support for customers who find themselves in financial difficulty.

In this sense, it seems to me that the volunteers at Mental Health Innovations act as a kind of augmented customer support team for Anglian Water.

How Anglian Water arrived at this decision

One big story around the water companies in recent years has been the pollution of the UK’s waterways and the rise of illegal sewage dumps, covered by news organisations such as the BBC and the Telegraph. This reached a head earlier this summer with a government-commissioned report recommending the abolition of the water regulator ‘Ofwat’ in a recognition that structural changes had to be made given these developments. This is the backdrop against which Anglian Water decided to launch its new mental health service in 2023.

The spokesperson explained to me on the phone how the company arrived at this initiative. During the cost-of-living crisis that followed the Covid-19 pandemic, Anglian Water trialled a customer support service via WhatsApp, which was well received. It turned out that many people preferred typing about their situation to speaking on the phone. Firstly, there is the convenience, but secondly people said they found it easier to express themselves in the (digital) written form than verbally. Thirdly, written communication can’t be overheard, so can be more discrete and private. Encouraged by the success of the WhatsApp customer service channel, Anglian Water decided to go one step further and launch the partnership with Mental Health Innovations.

East Anglia is a region characterised by poor mental health. The Anglian Water spokesperson tells me that prescriptions for antidepressants are nearly double the national average. Many villages, some of which are very remote, are prone to loneliness. But there is a second factor at play: the high proportion of properties purchased as second homes by wealthy individuals thins out the local population. In fact, official statistics show that North Norfolk has the second highest proportion of second homes in the UK after central London: almost one in every ten properties.

More than just corporate social responsibility

Some would argue that the decision to engage with a charity for a service like this is a classic case of a company engaging in corporate social responsibility (“CSR” for short). However, I don’t think that this is what is going on here. CSR typically involves a company donating money to a charity or carrying out fundraising itself on the charity’s behalf. This allows a company to promote itself for this work, but it doesn’t directly add value to the company’s products.

If this were traditional CSR, Anglian Water might have donated money to Mental Health Innovations and promoted their SHOUT service in their communications – but they would probably have done so using the term “SHOUT”. For me, the fact that they purchased a keyword from Mental Health Innovations means that something different is going on here.

Diagram representing the process of a commercial partnership with Mental Health Innovations (Image reproduced with the kind permission of Mental Health Innovations.)

For me, there are two central questions here:

1. Why does a water supplier feel responsible for the mental health of its customers?

2. Why do mental-health-based commercial partnerships exist for these companies?

Regarding the first question: I believe this is primarily due to the normalisation of discourse on psychological health in many areas of British society: in culture, at work, and in the family. Don’t get me wrong: this is a good thing. And against this backdrop, I can imagine that it actually feels quite ‘normal’ for a company to take an interest in the mental well-being of its customers to a certain extent – indeed, you could turn it the other way round and ask how, in today’s world, a company could not care about its customers’ wellbeing? Perhaps it is the logical extension of taking your employees’ mental health seriously. It is also part of a broad shift towards prevention, and prevention can be done by many people in many different contexts – indeed: the more, the better.

The current cost-of-living crisis, which is causing more and more people to struggle to pay their electricity or water bills, is definitely leading to a rise in mental health issues. Some would argue that it is the job of the NHS to tackle these issues (or even of the politicians to fix the cost-of-living crisis in the first place). But of course, the NHS is also in crisis, with waiting times to see mental health specialists increasing. Hence the argument that it is better to offer people something now than do nothing and make them wait months for an appointment. This is one reason why services like SHOUT emerge, and I think it is one reason why companies like Anglian Water want to do their bit, as it were, to help their customers.

But this doesn’t answer the second question, because they could also just have supported SHOUT as SHOUT, without their own keyword. Perhaps the short answer here is that all charities need to fund their work, and donations can only go so far. But what we are dealing with here is a product, and therefore we need to talk about user experience.

Valuable Mental Health Trends

For some time now, product development has been about making things that customers love. It’s about the feelings a product evokes – not just the problems it solves. This approach is now well established, and companies that are good at it, such as Apple and Spotify, have become hugely successful.

The business of emotions is nothing new. What is new to me, however, is the way in which I feel that negative emotions, so to speak, are being dealt with here. The idea that mental illness might contain potential for value-creation, or to put it another way, that engaging with mental illness, rather than just positive emotions, might become part of companies’ ways of creating value.

With its other service, ‘The Mix’, which is aimed at young people specifically, Mental Health Innovations promises commercial partners “valuable youth mental health trends and key insights” (the company states that 75% of its audience is aged 16-25). One might ask what these trends are and why they should be of interest to companies. (I contacted Mental Health Innovations, but they have recently been very busy preparing for World Mental Health Day.)

What is also new, I believe, is the digital nature of these engagements, with text messages replacing phone calls, which makes the data analysis easier and faster. As we saw, Anglian Water realised that many customers themselves feel more comfortable with digital written engagement compared to speaking on the phone. But of course without this digitalisation, the data analysis would be far more costly and potentially not financially viable as a service. (Some mental health professionals might also point out that seriously working on your mental health is not always going to ‘feel comfortable’.)

Conclusion

On their website, Mental Health Innovations states that its service SHOUT has conducted three million text message conversations since launching, and that 43% of respondents said they had no one else to talk to. Clearly, people have a need for some sort of support.

I think it is a good thing that British society has come so far in terms of attitudes regarding mental health that such services are made use of. Countries like Germany could certainly learn a thing or two from the UK about normalising attitudes to mental health and campaigns that contribute to this. The fact that a company like Anglian Water is investing resources in offering such a service to its customers shows how far the discourse on mental health has normalised in the UK.

At the same time, I believe there is cause for concern about the direction in which the mental healthcare industry in the UK is heading. Firstly, there is a risk that professional medical care might increasingly rely on voluntary care and that the government could reduce state-financed capacity and resources, pointing to these cheaper resources and their popularity. That said, this is only a risk and not a certainty. But volunteer-staffed initiatives are not the only option here: the practice of social prescribing, for example, is another innovative approach that is much more integrated with existing medical care provision.

Secondly, one might ask why mental health trends are of such interest to companies and what kind of products they want to develop using them. In terms of the keyword partnerships themselves, since these are no longer a matter of CSR, but rather of selling a product, a space may open up for becoming more creative in terms of what that product can be and how much value it can deliver. As long as Mental Health Innovations is the only organisation providing this service, there isn’t a market to speak of, and so there is little external pressure to experiment. But if the model proves successful, Mental Health Innovations may well soon face competition, and then we could well see a new dynamic emerge.

-

Hello. My name is Matthew O’Conner Lomas and I am a British-German writer based in Norwich. Welcome to my blog, where I collect articles that I write for both British and German audiences.

I also have a German-language podcast about equal parenting and gender equality which you can find at www.partnerschaftsbonus-podcast.de